A main task for Christian scholars is helping to redeem the hearts and minds of our friends and colleagues…and even our enemies. What we wish to say here is devoted to one aspect of that, the redeeming of minds. The redemption of the mind is of obvious relevance to those whose vocation is practiced in a culture that has institutionalized reflective thinking and the life of the mind. The redemption of the mind is closely associated with learning to "think Christianly" about everything. One area we would urge you not to neglect in your Christianly thinking is your academic discipline. Is there an aspect of your academic discipline where your Christian faith has relevancy or even overlaps?

************

There are many things a professor can

do to better understand how to “think Christianly” about her academic

discipline, but this article will focus on the importance of clarifying her own worldview as a Christian as a means to do that.

worldview as a Christian as a means to do that.

Once she begins to do this, she can more easily see how to remain coherent in her faith and other ideas (endnote 1). This can sound complicated and even onerous, but we believe we can mitigate that impression by mapping out some ways to think about this, hopefully without being overly simplistic.(endnote 2)

There is a valuable prize at the end of this task! This prize includes attributes of the life of a mature Christian mind, such as understanding, wisdom and integrity. We will help our reader to better grasp an overview of what it means to think Christianly about everything and especially her academic discipline.

Wee begin with a few working definitions. We use the term “worldview” to represent the way our minds organize influential beliefs so that they form a perspective on how we view the world as a whole and interpret it.

“Thinking Christianly” is a means to analyze our beliefs through the lens of what we think our faith is telling us. What exactly the Christian faith amounts to is sometimes controversial, but for our purposes we are referring to historical orthodox Christianity.

When we think about Christian faith in that historical sense, it follows that who Jesus Christ is and what he tells us, as well as what the Bible tells us, directly shapes what it means to think Christianly.

In a rough and ready way, this is captured in the Latin phrases: Fides Quarens Intellectum—faith seeking understanding, and Credo ut Intelligiam—I believe in order to understand. C.S. Lewis once put it this way: "I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else."

In order to help you visualize how this can be done—how belief forming mechanisms and our intellect are organized and could be organized—we will use some diagrams. Hopefully, this will allow us to dip our toes into the shallow end of the pool and from there we can begin to clarify, refine and offer guidance for the project (endnote 3).

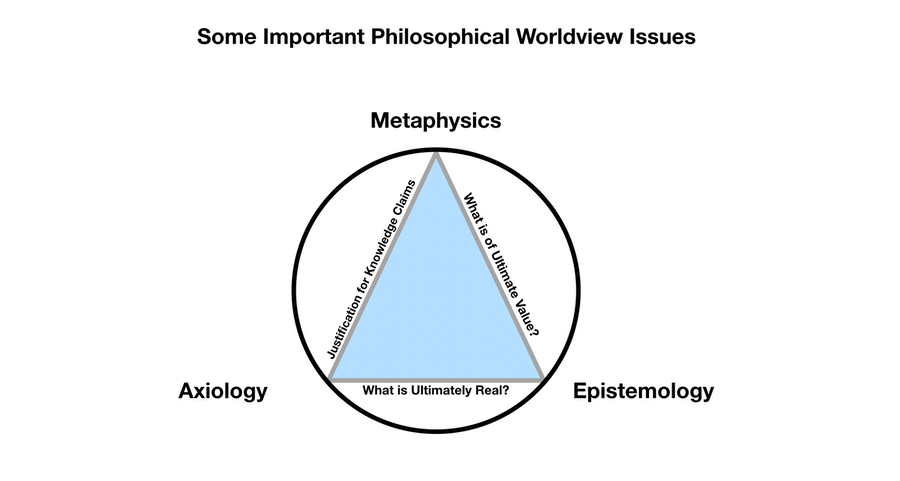

Through the centuries philosophers have

focused on three plausible areas of noetic organization: epistemology,

metaphysics and axiology. Each has technical meanings and domains, but for our

purposes let’s think of the contours of epistemology as having to do with

justification given for claims of knowing and knowledge. The domain of

metaphysics is much broader, but let’s say for our purposes it has to do with

what is real and what really exists. Axiology is the name we are using for the

category of our values and ethics. Our beliefs in these three areas can tell us a

great deal about how one thinks about a myriad of life orienting issues.

Through the centuries philosophers have

focused on three plausible areas of noetic organization: epistemology,

metaphysics and axiology. Each has technical meanings and domains, but for our

purposes let’s think of the contours of epistemology as having to do with

justification given for claims of knowing and knowledge. The domain of

metaphysics is much broader, but let’s say for our purposes it has to do with

what is real and what really exists. Axiology is the name we are using for the

category of our values and ethics. Our beliefs in these three areas can tell us a

great deal about how one thinks about a myriad of life orienting issues.

For many of us, our take on what these areas described above constitute is imbibed with our mother’s milk, our culture, and education. A lot of what we learn early constitutes what we later call common sense. The further we continue our education (college, graduate school, post-doctoral, etc.), we find ourselves re-shaping that worldview. In fact, one of the big lessons we are bequeathed from our education is that things are not always what they seem.

Within Western thought, Plato and Aristotle have had a great deal of influence in how we think about these areas because of their geographical location and because what we have of their work is more systematic than the pre-Socratic philosophers, not to mention the fact that they were extraordinarily competent, despite how ludicrous some of their work seems to our present sensibilities. The result is that their work has become coins of the realm in the discussion of these subjects. However, it should come as no surprise that though they shared common beliefs about the importance of these areas mentioned, they did not agree on many significant and substantive ways to construe them. As Christians we do not need to follow them or any other thinker slavishly, but it also makes sense not to ignore them or their legacy.

In light of this, how can we visualize our first approximation of what noetic structures look like? Here’s a quick sketch that paints a broad spectrum view that we’ll call "35,000 feet above the terrain” (endnote 4):

Figure 1

In the figure above you can see the three important categories we talked about above, organized to represent their presence in a well-formed individual noetic structure. That is, in a rudimentary way, epistemology is about justification for knowledge claims or, put in the form of a question, “how do we justify our claims to knowledge?” Metaphysics, in a similar way, is understood as answering the question, “What is Ultimately Real” and axiology as answering the question, “What is of Ultimate Value?"

How we think about and answer those questions will tell you a great deal about some of the most important questions that can be asked of anyone. For instance, probing someone’s beliefs in these three areas will reveal if a person is a theist or atheist, and whether she values honesty above personal gain.

Further, these basic conceptual coins will allow you to interact with our Hellenized western society. You could also ask the same questions as secondary questions in each of the academic disciplines. For example, you can ask people from each discipline how they know the particular conclusions they are forming in their work are justified, or how do they generally justify the knowledge claims they make. Asking the right questions will enable you to clarify what the dominant metaphysical system is in an academic field, allow you to ask what is the justification for that system and enable you to evaluate whether the justification is sound or not. Further, by asking the right questions, you can do more than just identify how their values and ethical systems impinge on what they study: you can also go deeper to understand how they are allegedly justified.

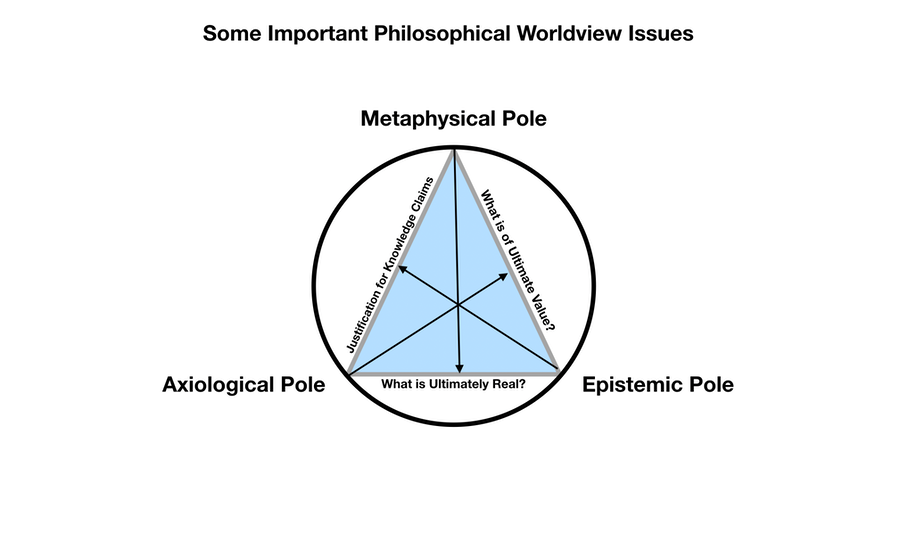

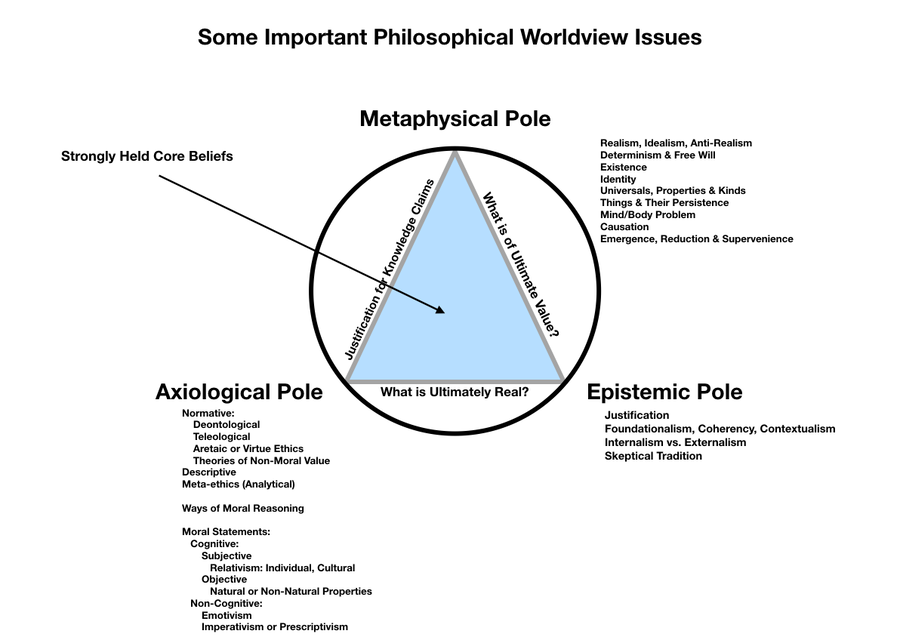

However, to see this, we need to fill in more details in our diagram and we want to do that in two steps, below. One step is to make a slight change and call each area a “pole” (to better express the idea of explaining their meaning by their projection across the diagram—Figure 2—and the second is to fill in more details on the range within each of those areas—Figure 3.

Figure 2

Figure 3

As you can see, there’s a lot more detail in Figure 3 (let’s say we’re moving in closer to about 30,000 feet), and the thing to focus on is that the lists adjacent to each pole represent sub-areas—each of which raises questions and therefore controversial elements that are subsumed in each larger category. They identify certain ways of thinking about diverse aspects in each pole area and how they might be construed. Some of these distinctions have to do with defining terms, some with methodology, and others with disparate ways the areas they represent are unpacked and explained.

You can see we’ve added an arrow in the last sketch, showing that the deeply ingressed beliefs we hold are held more firmly than others which are not as ingressed. That is, what we think about the sub-areas can make them become “control beliefs” for many other less strongly held beliefs, because these beliefs function in ways that can control other beliefs or control belief formation in certain ways.

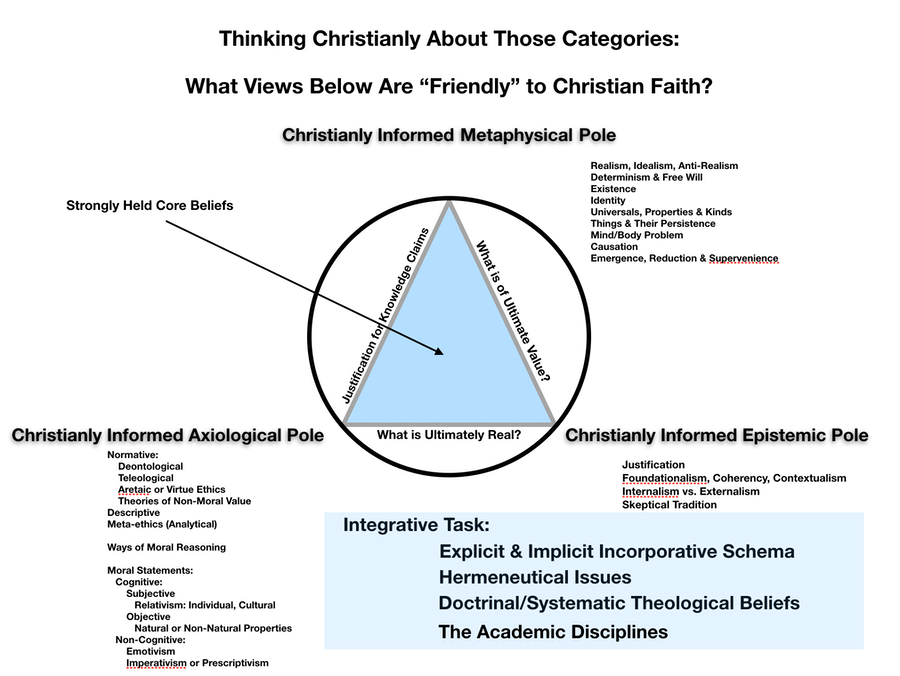

However, in this particular article, we don’t wish to say much too much more about those details; again, we are more interested in providing an overview of the whole project. Then we can ask, “what are some conceptions in these domains that are friendly to the Christian faith?”

To visualize this our next step is to sketch what that would look like from 25,000 feet.

Figure 4

If you have not begun any work for a better understanding of these areas, we provide resources on our website where you can begin your own reading. Try these links: Epistemology, Metaphysics, and Axiology. Using these links will open new tabs in your browser, but before you get into those details, there are some other things that need to be said.

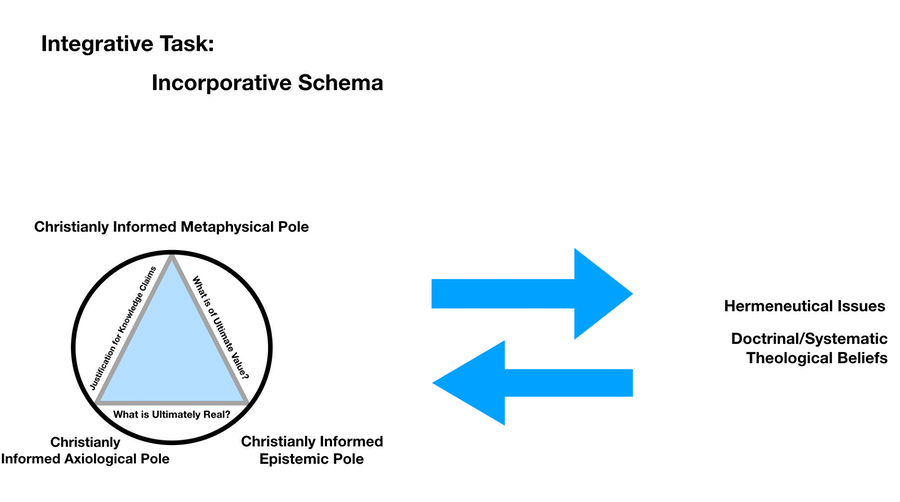

At the bottom right of Figure 4 (above) you will see a highlighted list of integrative tasks that are next steps to further explaining "thinking Christianly." We do not mean, as you will see, that you wait until you finish organizing your views in the academic domains before you do theology, rather that both aspects are done concurrently. Through iterations of development, we are looking to construct a sophisticated understanding of the three pole areas, informed by hermeneutical and doctrinal issues that come from our theology. See Figure 5 below:

Figure 5

This diagram illustrates the way the increasing knowledge of Christian theological data—aimed at the target of gaining theological acuity—is meant to interact with a growing understanding of these other domains. You will begin to see how this interaction informs important questions. What is a person? What constitutes our world? Is it a monistic, dualistic or some other kind of world? What does it mean to be made in the image of God? What do we mean when we say we “know” something theologically? We can ask of the disciplines, is it possible to justify beliefs formed by our cognitive faculties if God was not in some important way “behind” the design and processes that produced our faculties and that He was interested in us knowing things and not just surviving?

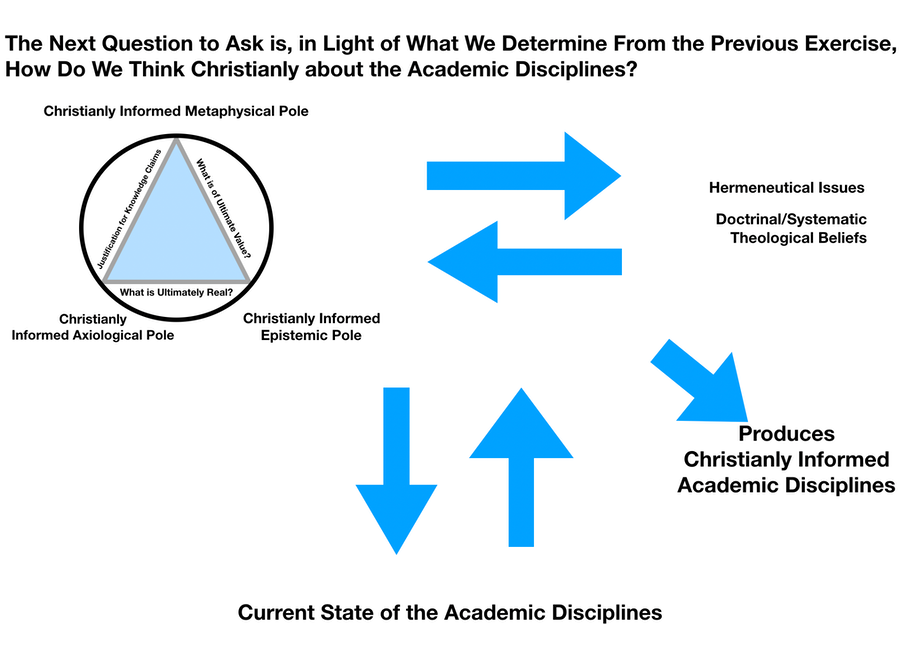

There is one more figure (below) we wish to highlight in this article. We hope it can help you visualize how the process of thinking Christianly about three important domains of thought can clarify your own worldview and through the interaction produce a Christianly informed view of the academic disciplines.

Figure 6

We think you can see where this is going. We strongly suggest that as we develop our understanding of our worldview and theologically interact with it, we can also begin to seriously think about the current and past state of the academic disciplines. What’s exciting is that you can do this with powerful tools to analyze, evaluate and critique the current and past “isms,” including and especially those who reside in your own discipline.

In our next issue of Connections Review we will continue with "Worldview and Thinking Christianly, part 2.” In that article, we’ll further discuss some of the details we’ve introduced here, fill in some explanatory gaps, and answer some critical analysis questions about what we have had to say. We’ll keep it as simple as we can, but you’ll find that we will also give you some of the tools to drill down deeper.

—Editor

________

Endnotes:

1 The good news is that you are not expected to complete this task in a day, a couple of months or even in a couple of years! It may take decades to reach the sophisticated level you will want to seek.

2 One advantage you bring to the table as a professor is that you are an expert in your academic field or discipline; and therefore likely have a great deal of background knowledge about how your discipline progresses. That is quite a leg up for the project we are talking about.

3 It should be clear that while we wish to try to think Christianly about everything, there are some things where Christianity doesn’t seem so relevant. For instance, I doubt there is much to be said about a Christian way to cut the grass, or the question of whether men’s shirts should have button down collars or not is informed greatly by our faith.

4 I want to acknowledge that the basic idea in the first sketch and its subsequent use in the article came from a class I took in seminary taught by Chuck Moore—about thirty years ago. That is, from him I got the basic idea of sketching the areas we are discussing within a circle and explaining their meanings on the sides of an inscribed triangle. I liked it because it could provide an useful way to partially visualize what clarifying a “thinking Christianly” worldview project looks like. However, what I am developing from there to visualize how the sub-categories can be analyzed and interact with Christian theology and the academic discplines are mine, including my being responsible for any errors.