I earlier suggested that I might oversimplify things a bit to get a first approximation; I did that because it’s easier to grasp. I’m going to continue to simplify things a bit in my discussion below. I trust you take advantage of the suggestion I made in the annotated bibliography to help you fill in the details, make the appropriate qualifications and nuances.

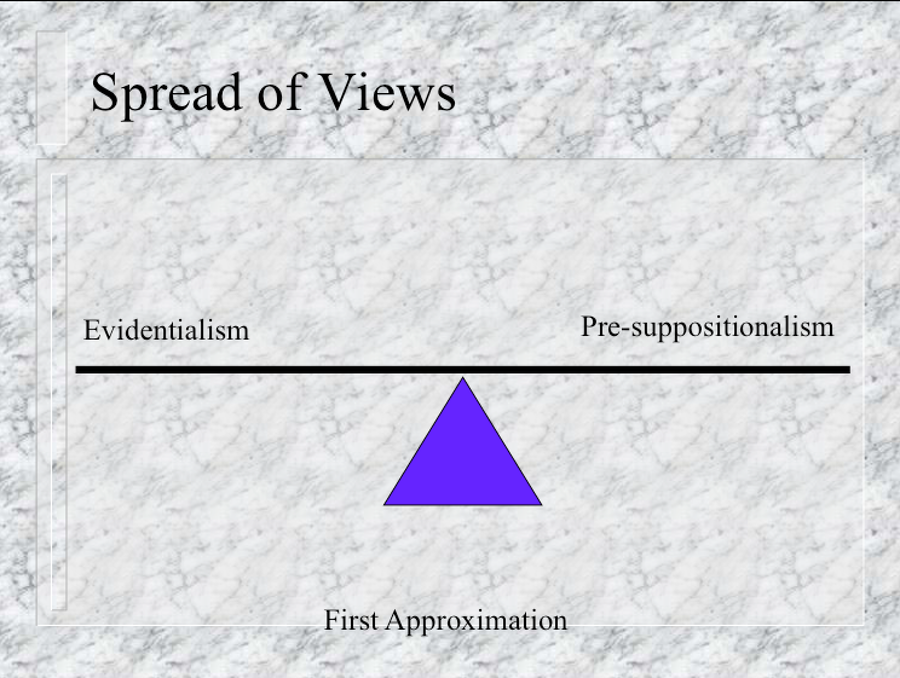

So let me begin with a diagram that can help illustrate a very rough and ready way, two ways of doing apologetics. This is represented below by a range of thinking about those two proper systematic way of doing apologetics:

Figure 1

In Figure 1, above, we can see that I’ve broken up systems of apologetics into two disparate camps: the evidentialists and the pre-suppositionalists. The evidentialists hold that a person is justified in holding a belief if and only if she has evidence for that belief and the evidence is both supportive and relevant to the conclusion and better than evidence than for the counter-factual (the opposite) state of affairs.

By contrast the pre-suppositionalist hold for various reasons, that all argumentation has to end somewhere and that in certain cases a person is justified holding beliefs that are not supported by any other beliefs or arguments. So, in this way of thinking about justification, you won’t argue propositionally for the truth of your presupposition because they are as low in your hierarchy of beliefs as you can go and everyone has to stop somewhere—but, you might defend your epistemic rights to hold the pre-suppositions or basic beliefs you do have.

So in terms of apologetics, the evidentialist camp typically tends to hold that a person is justified in believing that God exists or that Jesus is the Son of God or the Bible is the Word of God, if and only if that person has evidence for that particular belief and the evidence is relevant to that conclusion and is better than the evidence for the counter-factual.

The pre-suppositionalists (generally speaking), hold that a person is justified in believing that God exists or that Jesus is the Son of God or the Bible is the Word of God because that is their starting point of reasoning and those things cannot (like any other philosophical starting point) cannot be reasoned to. That’s why they say they are pre-supposed. Other’s in the camp hold those specified beliefs were “properly” basic beliefs--or beliefs that did not need further justification because they did not need to be supported by other beliefs or arguments to be held in a rational way. They can be believed and justified if those beliefs are formed in circumstances that are appropriate and their brains are properly functioning. Note: some presuppostionalists hold that God is a properly basic belief, but from then they argue to the other positions in their apologetric stance in an evidentialist way.

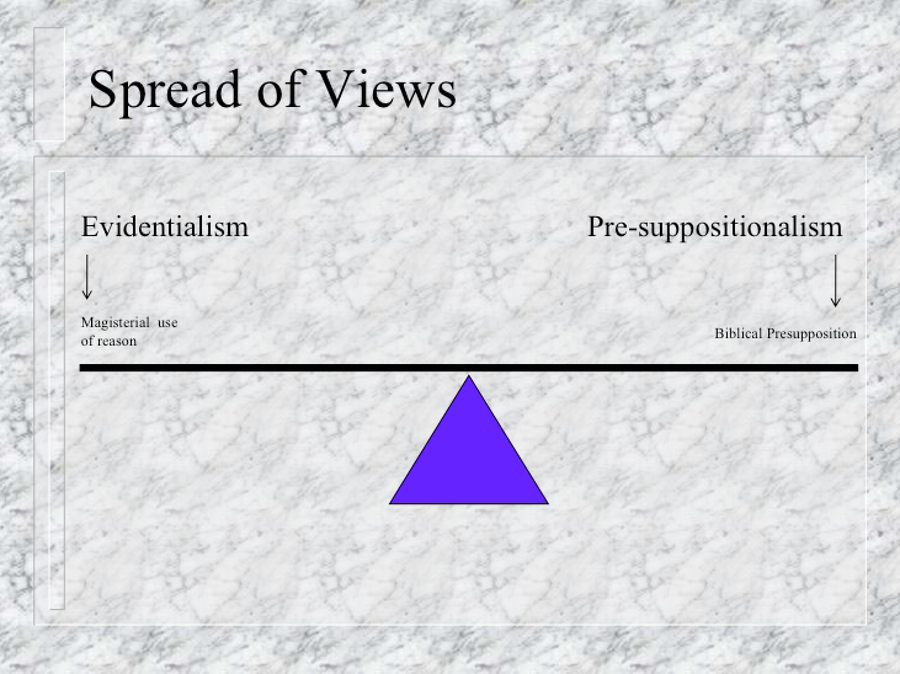

To help in understanding this, the diagram below shows two extreme positions taken by the evidentialists and the pre-suppositionalists (with a spectrum between them not yet filled in):

Figure 2

In this illustration (Figure 2), at the extreme of evidentialism would be the “magisterial use of reason” perspective that would hold that the arguments for the existence of God (or whatever) are so strong that a person who disbelieves has not done their epistemic duty (deontological) to believe, given the evidence.

At the other extreme in the diagram is the pre-suppositional view that is often called “Biblical" pre-suppositionalism because it presupposes the truth of the whole Bible. That is, this view holds that belief that the Bible is the Word of God is held as a basic presupposition—including all it teaches within it (as described above). That is, they believe they are entitled to those beliefs and do not need any other supporting evidence or arguments because everyone is entitled to their pre-suppositions…and everybody else has theirs. Since (some) them say no one can argue to their presuppositions, they claim they are in no worse epistemic position than any other.

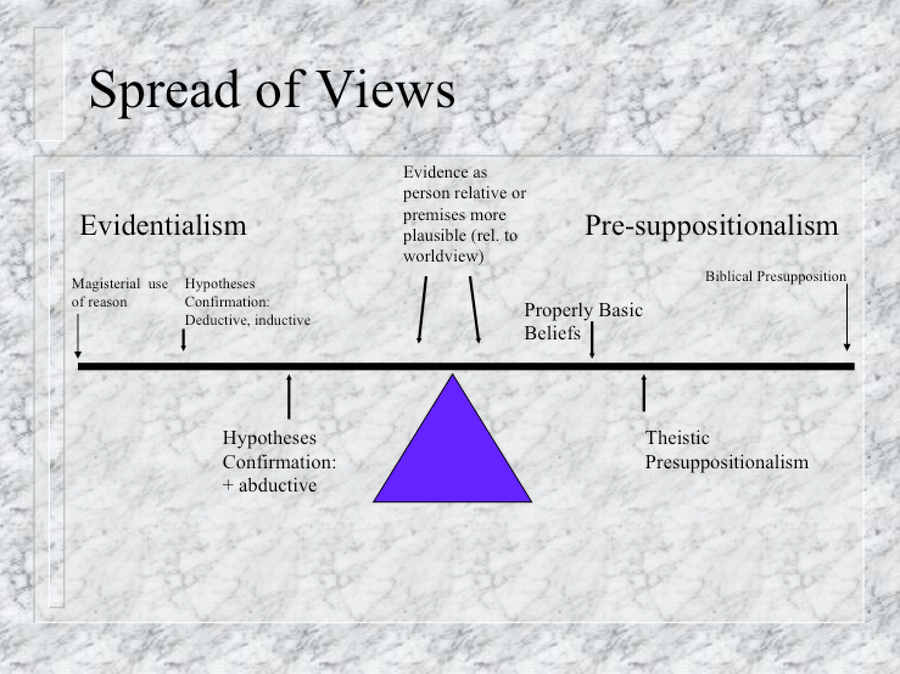

From this basic illustration of the extremes, you could now fill in a range of views on that spectrum—see below.

Figure 3

Suffice it to say that those towards the center of the diagram, in various ways, take less expansive stands, but still in the tradition of the two basic justification camps. For further details, explore the two other tabs: "Evidentialism Explained" and "Presuppositionalism Explained.”